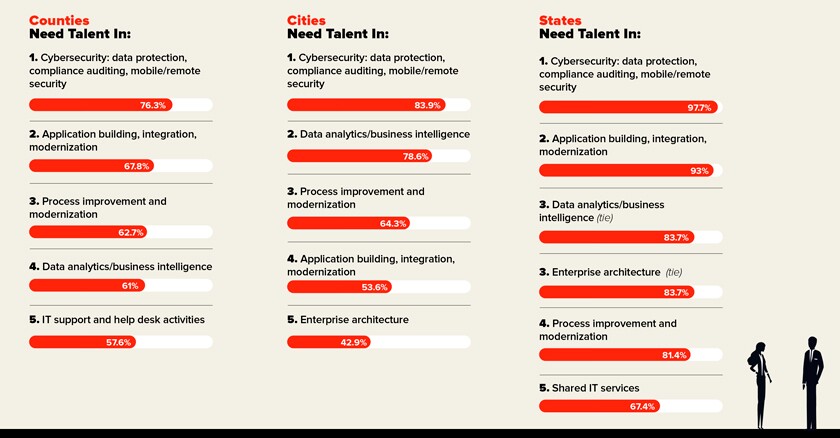

At the county level, survey respondents say they will need help with application building and integration (67.8 percent); data analytics/business intelligence (61 percent); and process improvement and modernization (62.7 percent).

State and city IT leaders point to these same areas, with varying degrees of urgency. Only half of city IT teams (53 percent) say they are short on application-building talent, for example, while 93 percent of state technology organizations see a need here. In other areas, such as data analytics, government at all levels finds itself shorthanded.

“I have an IT department, a GIS [geographic information system] department and a broadband utility — and they all have vacancies at the moment,” said Michael Blanchard, director of technology services in Columbia County, Ga. “We and a lot of other local governments are hurting not just in cyber, but in the traditional IT roles — the database administrators, the system administrators, the people who you need in order to make your network work.”

State and local agencies are under pressure to close IT workforce gaps in order to move forward on their most pressing agenda items.

“Addressing current and future needs when it comes to cloud, digital services, citizen-facing services — those are the big things that CIOs are working on right now,” said Meredith Ward, deputy executive director of the National Association of State Chief Information Officers (NASCIO).

Does this job really require a four-year degree? If it does, great. But if it doesn't, let's look at that. Flexibility is the name of the game.

In order to meet that mission effectively, IT leaders at the state and local levels are putting in play a variety of strategies. Some are tentatively considering the use of managed services as a way to bridge the shortage. There’s continued movement to shift job qualifications, leaning more on certifications and less on four-year degrees. And most IT organizations are getting more proactive and more creative in the way they build their talent pipelines.

At the same time, many IT leaders are working harder to retain the staff they already have in place. “They may be offering some sort of remote, hybrid, flexible work schedule, or focusing on diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging,” Ward said. “The majority of the workforce in this country these days are the millennial generation, and those are things that are important to them.”

Center for Digital Government

MIXED FEELINGS ON MANAGED SERVICES

Faced with persistent workforce shortages, one might suppose that state and local IT shops would embrace managed services as a means to bring in as-needed talent, a way to shift the operational burden. In fact, many are reluctant to take this approach.

North Dakota CISO Michael Gregg, for example, typically will shy away from outsourcing, preferring to build a more robust and resilient in-house team. “I’d prefer to have a path to grow my talent that I have internally,” he said.

In Columbia County, Blanchard voiced similar concerns, citing cultural reasons for the county’s relatively limited use of managed services. “Our county manager has worked very hard to foster a culture of family and belonging,” he said. “We want people to be part of the team and not to be just a mercenary or a ‘hired gun,’ so to speak.”

There are pragmatic reasons, too, for being cautious in the use of managed services. Some in state and local government see the risks potentially outweighing the rewards when it comes to using outside help.

With a lot of the computer science degrees, the computer information degrees, you learn a little bit of everything in the computer field. You learn some programming, some networking. But that doesn’t necessarily help with what we’re looking for.

Gregg shares that concern. “You have to spin up those individuals — especially if they haven’t worked in state or local government before, if they don’t understand the organization or the entity,” he said. And then, once you’ve made that investment in training, “they may find a better deal somewhere else, and then you’re left doing that again.”

Some say that when it comes to managed services, other risks factor in as well. In Ohio, for example, the most urgent IT needs are around cybersecurity, and that’s exactly the area where state CIO Katrina Flory is especially leery of involving an outside organization. She expressed concern that third-party involvement with cyber might not be a smart play for the state.

It’s a worry that others share, Ward said. “When it comes to cybersecurity, even if you are outsourcing something, the risk never leaves the state,” she said.

Outside entities may assume responsibility for an IT task, but the state or city still will be liable if anything goes wrong — a fact that often works against the use of managed services. “The CISOs who are in charge of cyber are a pretty risk-averse group,” Ward noted.

Gregg cites this as a reason to be wary of doling out work to others. Across a range of IT tasks, “you can outsource the activity to a third party, but ultimately you’re still responsible,” he said.

Given these lukewarm feelings toward various forms of outside assistance, state and local agencies likely will focus on building up their internal teams. Increasingly, they are looking to do that by re-evaluating their hiring criteria. In IT, the notion of a bachelor’s degree as the price of admission is fading fast.

THE NEW STANDARD

In Avondale, Scheetz has reconsidered his job descriptions and opened up a range of IT roles to those with certifications and other qualifications, rather than requiring a four-year degree. In many cases, “we’re good with experience, or maybe some community college plus some experience,” he said.

If someone doesn’t have a degree, we’re able to consider experience instead. That really widens our applicant pool. We’re able to tap talent that may come through nontraditional types of pipelines, and it’s been a huge benefit to us.

Blanchard has worked in organizations that required a bachelor’s degree, “and it made hiring difficult at times, just because we had a very small applicant pool,” he said. For entry-level jobs and even some mid-level positions, he’ll hire based on a mix of experience and certifications. “That has long been the policy for Columbia County, and it’s been successful.”

At the state level, too, the needle is swinging this way. Ohio, for example, revised its administrative code back in 2012 so that qualifications are no longer stated in terms of academic degrees.

“If someone doesn’t have a degree, we’re able to consider experience instead,” said Kitty Hollingshead Mancil, Ohio’s state talent management director. “That really widens our applicant pool. We’re able to tap talent that may come through nontraditional types of pipelines, and it’s been a huge benefit to us.”

In North Dakota, Gregg has likewise leaned hard in this direction. “We used to have four-year degree for everything, depending on the role,” he said. “One of the first things I did when I came in was to change our requirements. Now that can be a two-year degree or a certificate. If they’re hungry and they want to learn, we can certainly teach them.”

That strategy helps him to be more competitive with private industry. In the private sector, people may get slotted into a particular role early on. Gregg, on the other hand, will take these minimally skilled individuals and offer them broad-based training in areas like automation, access control and incident response.

“We get them involved, and we build up this broad skill set,” he said. “As their skills increase, we can give them more responsibility, more breadth of work.”

At NASCIO, Ward sees this trend playing out nationwide. “States are recruiting from two-year degree programs, from certification programs,” as well as among mid-career individuals with no IT background, she said.

“If you have a willingness to learn and you have a willingness to do the work, states want you,” she said. Not all jobs will be open to those with just certifications, experience or enthusiasm, but states are winning when they drop their one-size-fits-all approach. “Does this job really require a four-year degree? If it does, great. But if it doesn’t, let’s look at that. Flexibility is the name of the game.”

BUILDING THE PIPELINE

To meet the challenges of the day, state and local IT leaders have embraced a range of creative recruiting strategies.

Partner with higher ed: While colleges and universities have long been rich sources of IT talent, many government agencies are doubling down on their engagements with higher education in order to get an edge in today’s highly competitive environment.

In North Dakota, for example, Gregg serves on the advisory boards of multiple colleges and universities. He’s helping to ensure that the curriculum aligns with the skills the state needs. “Some schools are still teaching stuff that’s three or five years back: edge devices, firewalls,” he said. “We’ve worked very hard throughout the state to try to get alignment on them teaching the skills that we need not only in the government sector, but also in private industry.”

City-level IT leaders likewise look to higher education. Scheetz, for instance, has contact with individuals at local universities and community colleges, people who keep an ear to the ground on his behalf.

“They know the students who are going to graduate and are looking for a job. They also have their list of recent grads. They bring students forward every so often,” he said. “They’re helping those students, and it works out well for us, too.”

Look to internships: Intern and apprentice opportunities are another productive avenue for recruiting. Ohio, for example, has programs at the high school and community college levels.

“That started as a way to recruit folks who were not necessarily working toward a four-year college degree,” Flory said. It’s a way to connect with people “who would meet [alternate] qualifications to apply for our full-time positions.”

If we have employees who are dedicated civil servants, who are interested in moving into different positions and continuing their career, we really want to be able to support that.

“We have about an 80 percent placement rate, meaning after they do an internship with us, they stay and work for North Dakota,” he said. “For individuals who are mission-driven, they’re going to connect to this. Then, as those roles come open, we can transition them in.”

He’s presently looking for state Senate approval to expand the apprenticeship program. “Should this be approved, then we will spread these apprenticeships not just in the security team, but across all the other technical teams,” he said. “By helping them learn those skills, and getting them introduced to the mission-driven work, we can retain a lot of that talent and fill a lot of this need that way.”

Be opportunistic: There’s a lot of talent out there, but IT leaders need to be strategic in their sourcing.

In Ohio, layoffs at a large company presented a window of opportunity. Flory’s team participated in a job fair for those being laid off and was able to put the state’s opportunities in front of some 500 people.

“The technologies that we use are in alignment with what they were using,” she said. “So we talked to them about what we do at the state of Ohio, and where they can come on board and make a difference.”

Ohio also is looking to recruit career-changers into IT, especially those who already have a track record in state government. “If we have employees who are dedicated civil servants, who are interested in moving into different positions and continuing their career, we really want to be able to support that,” said Hollingshead Mancil.

In Avondale, Scheetz likewise is looking for those who are seeking a change. “Someone may be in a junior role and they don’t see that opportunity to grow in their company where they’re at today,” he said. “They’re looking for that next opportunity, and they are bringing great skill sets.”

Recruit military: In Columbia County, the proximity of Fort Gordon creates an opportunity for Blanchard to reach out to the ex-military community.

“We’ve hired some ex-military people recently through reaching out to the local military base as well as to the local universities, because a lot of military people get out and they stay local: They go to school here and they don’t want to go back into that military environment. So we put ourselves out there as a viable alternative,” he said.

Former military members can be an especially good fit for government. “They’re looking for something else to do, and serving their community is a natural progression from serving their country,” he said. “Those are people that have service in their background and in their blood.”

Lean on automation: Even as they work to fill vacant positions, some in state and local government are turning to automation to help close the gaps.

With bots and automated scripts, “we can free up those individuals that were in those types of roles, and can reassign them to more productive work,” Gregg said.

As the organization in North Dakota has grown from 20,000 to over 200,000 endpoints, “I need to get that coverage from the same amount of staff and resources that the state has already provided me,” he said.

To that end, “I have leaned heavily into AI to automate many of our lower-end activities or tasks,” he said. “For example, we’ve highly automated our phishing response with AI and machine learning, and we have been able to cut our mean time to respond while also freeing up those individuals for other tasks.”

Leverage social media: While most IT organizations have used LinkedIn and other social media tools to get the word out, Scheetz has doubled down on this by making it a collaborative effort along with other state agencies.

“As a city, we do really well cross-promoting each other’s jobs. The various directors will post on LinkedIn and if I post something, another director will pick it up and share it or ‘like’ it. It just helps expand that network,” he said. “It doesn’t take a lot of effort on the director’s part, and it really gets us out there.”

Taken together, these strategies can help to close the government IT workforce gap, something that virtually everyone in the public-sector arena is eager to address. Across government, IT leaders “are focused on workforce — current needs, future needs and how they’re going to deliver services,” Ward said.

In some cases, the ability to meet that bar will depend on simple dollars and cents.

“I’ve seen a lot of states that have been successful in raising salaries for all of their employees, especially after the pandemic,” she said. “While we know that salaries aren’t everything, it is obviously important. None of us goes to work for free every day.”

*The Center for Digital Government is part of e.Republic, Government Technology's parent company.

This story originally appeared in the July/August edition of Government Technology magazine. Click here to view the full digital edition online.